I really enjoyed this article – it confirmed something I already knew, and that was that dysbiosis, or imbalances in gut bacteria, can cause problems with mood, such as depression. Knowing that many of our brain chemicals are produced in out digestive tract, it makes sense that a disruption of the good bacteria can influence how we feel.

From analysing hundreds of Complete Digestive Stool Analysis tests, I have found two very interesting correlations. One is that I believe stress can kill off our good bacteria, especially our Bifido bacteria which seems to be very sensitive to stress, and the second pattern I have seen is depression when there are low levels of the good strain of E-Coli. Rebuilding the good bacteria in the gut is paramount in any mood disorders…

Gut instinct – Bacteria and behaviour

Tantalising evidence that intestinal bacteria can influence mood

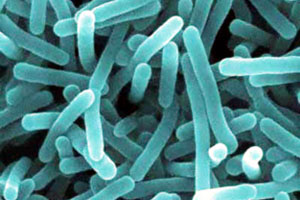

A GOOD way to make yourself unpopular at dinner parties is to point out that a typical person is, from a microbiologist’s perspective, a walking, talking Petri dish. An extraordinary profusion of microscopic critters inhabit every crack and crevice of the typical human, so many that they probably outnumber the cells of the body upon and within which they dwell.

The researchers, led by Javier Bravo of University College, Cork, split their rodent subjects into two groups. One lot were fed a special broth containing Lactobacillus rhamnosus, a gut-dwelling bacterium often found in yogurt and other dairy products. The others were fed an ordinary diet, not fortified with microbes.

The team then subjected the mice to a battery of tests that are used routinely to measure the emotional states of rodents. Most (though not all) of these tests showed significant differences between the two groups of animals.

One test featured a maze that had both enclosed and open tunnels. The researchers found that the bacterially boosted mice ventured out into the open twice as often as the control mice, which they interpreted to mean that these rodents were more confident and less anxious than those not fed Lactobacillus.

In another test the animals were made to swim in a container from which they could not escape. Bacteria-fed mice attempted to swim for longer than the others before they gave up and had to be rescued. Such persistence is usually interpreted by students of rodent behaviour as evidence of a more positive mood.

Direct measurements of the animals’ brains supported the behavioural results. Levels of corticosterone, a stress hormone, were markedly lower in the bacteria-fed mice than they were in the control group when both groups were exposed to stressful situations. The number of receptors for gamma-aminobutyric acid, a natural chemical messenger that helps dampen the activity of certain nerve cells, varied in statistically significant ways between the brains of the two groups, with more in some parts of the treated animals’ brains and fewer in others. Most intriguing of all, when Dr Bravo cut the animals’ vagus nerves—which transmit signals between the gut and the brain—the differences between the groups vanished.

The idea that gut-dwelling microbes can affect an animal’s state of mind may strike some people as outlandish, and there are certainly loose ends still to be tied up. Beyond their evidence that the vagus nerve is crucial to the relationship, for example, Dr Bravo and his colleagues do not yet know the precise mechanisms at work. There is also an obvious follow-up question: whether a similar thing is going on in people. A few previous studies have hinted at the possibility. For example, bacterial treatments may help with the mental symptoms of illnesses such as irritable-bowel syndrome.

All this is forcing a reassessment of people’s relationship with the bacteria that live on and in them, which have long been regarded mainly as a potential source of infections. An editorial in this week’s Nature raises the possibility that the widespread prescription of antibiotics—which kill useful bacteria as effectively as hostile ones—might be one factor behind rising rates of asthma, diabetes and irritable-bowel syndrome. If Dr Bravo’s results apply to people, too, then mood disorders may end up being added to this list.

Leisa

![]()

1 commentAdd comment

Yes there is a definite connection between mood and gut bacteria which I have seen in my own family as well as with clients. The Gut and Psychology Syndrome Diet (GAPS) was created by Dr Natasha Campbell – McBride and successfully addresses rebalancing our inner ecosystems and correcting psychiatric and neurological disorders by improving gastrointestinal function. Lots of useful information can be found at http://www.gaps.me. One of the easiest ways to repopulate your gut with good bacteria is by consuming cultured foods.